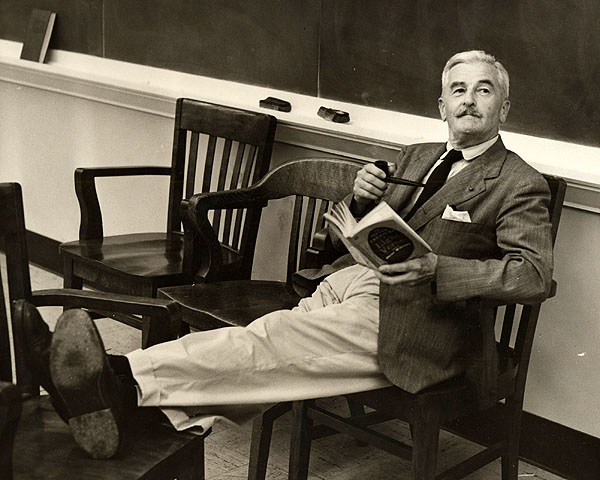

William Faulkner: A Southern Tempest of Words and Whiskey

American writer and novelist William Faulkner, born Falkner, made his foray into the literary world with poetry but gained prominence for his novels set in the ethereal Yoknapatawpha County in the Deep South, in particular his novel “Sartoris.”

American writer and novelist William Faulkner, born Falkner, made his foray into the literary world with poetry but gained prominence for his novels set in the ethereal Yoknapatawpha County in the Deep South, in particular his novel “Sartoris.”

William Faulkner is now considered one of the greatest American Southern literature writers, though he was a relative unknown for much of his career until he received a Nobel Prize for Literature in 1949.

Faulkner, who dropped out of school and took odd jobs at a bank and for a carpenter, had a variety of success including an adaptation of his “Sanctuary” novel – at that time very controversial – into a full feature film by a Hollywood studio. His “The Sound and the Fury” rests as the sixth-best English-language novel of the 20th century according to the Modern Library.

He was born in Oxford, Mississippi on September 25, 1897 and would die on July 6, 1962, of a heart attack in Byhalia, Mississippi. Shortly before his death, he went on to win a second Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for “The Reivers.”

He was posthumously awarded a National Book Award for his “Collected Stories.”

Writing Style and Publications

While his early works centered on poetry and drawing, Faulkner began writing novels and short stories in the early 1920s. This poetry background is credited for Faulkner breaking from the conventions of his day by using a longer cadence and deeper diction.

Instead of adopting the popular minimalist style, Faulkner applied a “stream of consciousness” style that includes emotional appeals, subtle weaving of themes throughout multiple stories, incredibly complex character motivations, and sometimes grotesque (in the dark, literary sense) themes.

Faulkner was not afraid to deal with Southern concerns and social politics that were still fresh in the minds of U.S. citizens. These portrayals added a breadth to American understanding of the multifaceted influences behind the class structure of the South: from former slaves and their children to whites who were poor, farmers, lower-middle class or Southern aristocrats.

His first two novels were written in New Orleans and the house he worked in at, 624 Pirate’s Alley, is now the home of Faulkner House Books. It is a short distance from the famous St. Louis Cathedral, which biographer Randy Nelson said provided him some inspirations in the early days.

He crafted and published 13 novels from 1920 through the start of World War II, a break-neck speed that included some of his most famous novels:

- “Sartoris”, published in 1928;

- “The Sound and the Fury”, published in 1929;

- “As I Lay Dying”, published in 1930; and

- “Absalom, Absalom!” published in 1936.

This time period also included his first collection of short stories with the 1931 publication of “These 13.” This included the popular “A Rose for Emily”, “Dry September”, “Red Leaves”, and “That Evening Sun”.

Many of these works took place in Yoknapatawpha County which Faulkner modeled after Lafayette County in both temperament and geography – this is the real county that covers his hometown of Oxford, Mississippi.

Faulkner returned to this location for his trilogy of novels covering the fictional Snopes family of prominence in Mississippi: “The Hamlet” (1940), “The Town” (1957), and “The Mansion” (1959).

When remarking on his work in 1956, Faulkner told The Paris Review that a writer should “take up surgery or bricklaying if he is interested in technique. There is no mechanical way to get the writing done, no shortcut. The young writer would be a fool to follow a theory.”

Personality like a Strong Drink

Perhaps best summing up his own approach to writing and his own force of nature, Faulkner also said in his interview with The Paris Review: “The good artist believes that nobody is good enough to give him advice. He has supreme vanity. No matter how much he admires the old writer, he wants to beat him.”

Faulkner is also well known for his ability to drink and his propensity to go on benders once he finished a work. He also famously took to the skies in a biplane with a heavy amount of bourbon in his system and in bottles next to him. While he performed some of the most difficult biplane maneuvers, he would end up crashing his plane into a hanger’s roof, giving him a limp for years afterward and a permanently bent nose.

He defined himself by his work, and while he harkened back to his heritage for perspective and influence for his psychological paradoxes and master works, he was fluid in his self-definition if it did not align with his writing.

According to a biography by Nelson, Faulkner made the change to his name – adding a “u” to his original Falkner – in 1918 through no major decision beyond how it impacted his work. Nelson writes that a typesetter made an error and added the “u.” When Faulkner saw it and was asked if he wanted a change, he replied “Either way suits me,” and the official change happened shortly thereafter, writes Nelson.

After the publication of “Sartoris” in 1928, Faulkner presented himself as an author independent of publishers, branching out into freer content structure and being more vocal with criticisms of the publishing structure.

For his next novel, Faulkner forbade his agent from adding any punctuation that would clarify his meaning or perform any editing whatsoever. His writing was his essence, and Faulkner routinely worked odd jobs – from house painting to flying airplanes – all in pursuit of money to keep his writing.

Becoming a Writer

When Faulkner was living in New Orleans, Faulkner met and spent time with Sherwood Anderson, a novelist and short story writer. Faulkner and Anderson would go on excursions through the city and speak with strangers to hear their stories.

Anderson would leave Faulkner in the afternoons to write while Faulkner would ramble about or pick up work, the author once recounted. It was this time schedule that attracted Faulkner to writing and prompted him to try his first novel.

Faulkner then began to seclude himself as he worked on “Soldier’s Pay” and was at last confronted by Anderson who was worried that there was an unknown falling out with Faulkner.

“I told him I was writing a book. He said, ‘My God,’ and walked out,” Faulkner told The Paris Review.

When the work was finished, Anderson helped Faulkner get his book published on the single condition that Faulkner wouldn’t make Anderson read and edit the manuscript.

From then, Faulkner said he only needed a few things to stay on as a writer: “a place to sleep, a little food, tobacco, and whiskey.”

Personal Stories

In his teenage years, William Faulkner fell for Estelle Oldham. They dated for some time, but Estelle ended up dating other men and eventually married Cornell Franklin.

Franklin was a law graduate and a major in the Hawaiian Territorial Forces with ties to Estelle’s family, so the two married in 1918. In April of 1929, however, the two divorced.

William Faulkner returned and married Estelle in June 1929 just outside of Oxford. After a honeymoon to the beach, they purchased the Rowan Oak estate and moved in. Estelle would remain at Rowan Oak even after the death of William. After Estelle passed away in 1972, the University of Mississippi purchased the home.

William Faulkner is known to have had several extramarital affairs. While working on scripts for Hollywood, Faulkner had a tryst with a secretary and script girl Meta Carpenter. From 1949 to 1953, Faulkner had an affair with Joan Williams – this would later become the subject of Williams’ novel “The Wintering”, published in 1971.

Perhaps his most striking affair was with Else Jonsson. Else learned of Faulkner’s work from her late husband Thorsten Jonsson a New York journalist who interviewed Faulkner in 1946. Thorsten, who passed away in 1950, is credited as the man who introduced Sweden to Faulkner is likely the driving force behind Faulkner’s receipt of the Nobel Prize.

The Dagens Nyheter paper recently released some of their love notes and filled in the narrative of how the relationship between Faulkner and the widow Jonsson played out. Most notably, the paper says that at the banquet where for the first two met for the first time, the publisher Tor Bonnier credited Thorsten for working to secure Faulkner the honor.

Faulkner destroyed all of the letters that Else wrote him before he died. She would send them to the New York office of his Random House publisher and to his Hollywood home. His aim was to prevent his wife from learning of the affairs, but news reached her soon after it began.

The Nobel success came shortly after Faulkner published “Intruder in the Dust,” a story concerning a black man falsely charged with murder. He sold the rights of the story to MGM for $50,000, according to Biography.com.

In 1961, as Faulkner began to struggle with his health and willed away his manuscripts, books, letters, and other personal writing to the William Faulkner Foundation at the University of Virginia. Faulkner served as Writer-In-Residence for the University of Virginia from 1957 until his death in 1962, when he passed away from a heart attack.

Sources:

- Nelson, Randy F. The Almanac of American Letters. Los Altos, California: William Kaufmann, Inc., (1981)

- http://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4954/the-art-of-fiction-no-12-william-faulkner

- http://spacing.ca/toronto/2012/09/18/william-faulkner-drunk-in-the-cockpit-of-a-bi-plane-in-toronto

- http://www.biography.com/people/william-faulkner-9292252

- http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1949/faulkner-bio.html

- http://www.dn.se/dnbok/en-karlekshistoria-i-nobelprisklass

Bruce Watson

One of America’s greatest American Southern literature writers?” Please. Faulkner was, as has been said, not a great Southern writer but a great writer who happened to be Southern. He was one of America’s greatest writers. Period.

Megan

I luckily chose William Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury as my senior author project for my AP Lit. class. Getting to learn more about him and his life has been such a blessing. He was truly a great man and a insanely gifted writer. Although I’ve read most of his works at this point, The Sound and the Fury still remains my favorite!

H.L. Dowless

He might have been born in America, but he was Southern by the grace of God. Damn the enemies of the South!